WIP

MA Architecture, Year Two

January 2016

Royal College of Art, London

NEW TYPES OF VEHICLES

t’s 2025 and the Mayor of London’s pledge to fully-automate the London Underground has been successfully realised.Unfortunately, the steady increase in population (and car sales as a result) means that - above ground - London's road network is ever more saturated with angry and reckless drivers.

Ford finally releases its first commercial driverless car with the Protect Your Family campaign: a car programmed to put the safety of its passenger(s) as the foremost priority. Road casualties in London have risen to 40,000 a year and the car is strategically released right after a string of heavily-covered car-related fatalities.

As more people opt into the safety guarantee, Ford’s promotion of self-interest is criticised - no thought is being given to the consequences this sort of vehicle might have on its surroundings. If car manufacturers can provide control over an accident's outcome, then surely the passenger should be offered more freedom in choosing its fate.

Ford subsequently releases a series of new campaigns that allow its customers to decide for themselves what sorts of ethics they want their driverless vehicle ought to function by.

The DVLA enforce a new law whereby the visibility of programming possibilities is made mandatory. A new code of symbols is introduced and manufactured as a car accessory.

Ford finally releases its first commercial driverless car with the Protect Your Family campaign: a car programmed to put the safety of its passenger(s) as the foremost priority. Road casualties in London have risen to 40,000 a year and the car is strategically released right after a string of heavily-covered car-related fatalities.

As more people opt into the safety guarantee, Ford’s promotion of self-interest is criticised - no thought is being given to the consequences this sort of vehicle might have on its surroundings. If car manufacturers can provide control over an accident's outcome, then surely the passenger should be offered more freedom in choosing its fate.

Ford subsequently releases a series of new campaigns that allow its customers to decide for themselves what sorts of ethics they want their driverless vehicle ought to function by.

The DVLA enforce a new law whereby the visibility of programming possibilities is made mandatory. A new code of symbols is introduced and manufactured as a car accessory.

If no human attention is required for navigation, the car’s interior can become a space to live in and sleep in, as well as travelling in.

PORTRAIT

If the efficiency of driverless technology reduces road area by half, dominating inner-city infrastructures that are symbolic of the 20th century may offer a better role within the city.

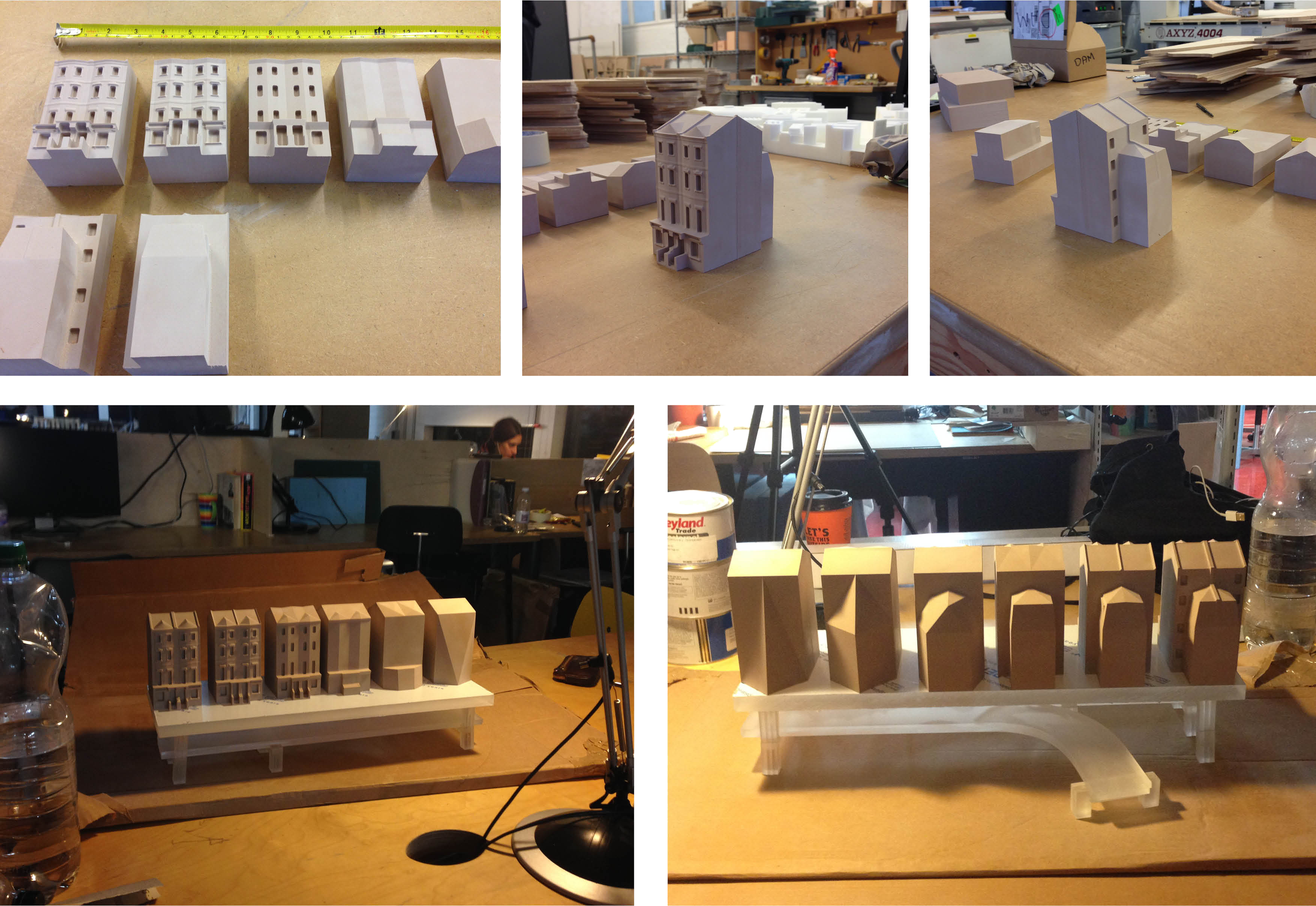

SCALE MODEL

The Universal Texture is an example of how virtual space is starting to have spatial implications. It’s a 3D mapping system that collects and compiles vector data, processes it, and applies it to a virtual model of the earth.

The power this model as a visual and navigational tool is compelling. At its best it allows us to enter into an immersive virtual reality where our spatial experiences are enhanced. Its misinterpretations of the real world reveal where the logic behind the system fails. Features and characteristics that seem obvious to humans escape machine vision – bridges sag tiredly over their span and trees become solid green balls.

Most computer users have grown up with Google Earth and its evolving yet unmistakeable aesthetic. Today, in its fifteenth year of existence, it cannot be denied that although imperfect, the infinitely-updated earth has a strong impact on how many of us experience cities.

We also accept that, actually, the low resolution offered to us provides sufficient description of its content – you don’t need to see individual bricks or lead roofing to recognise a terrace house. This model questions how many parameters are needed for recognition to remain.